Transitioning to Open-Source

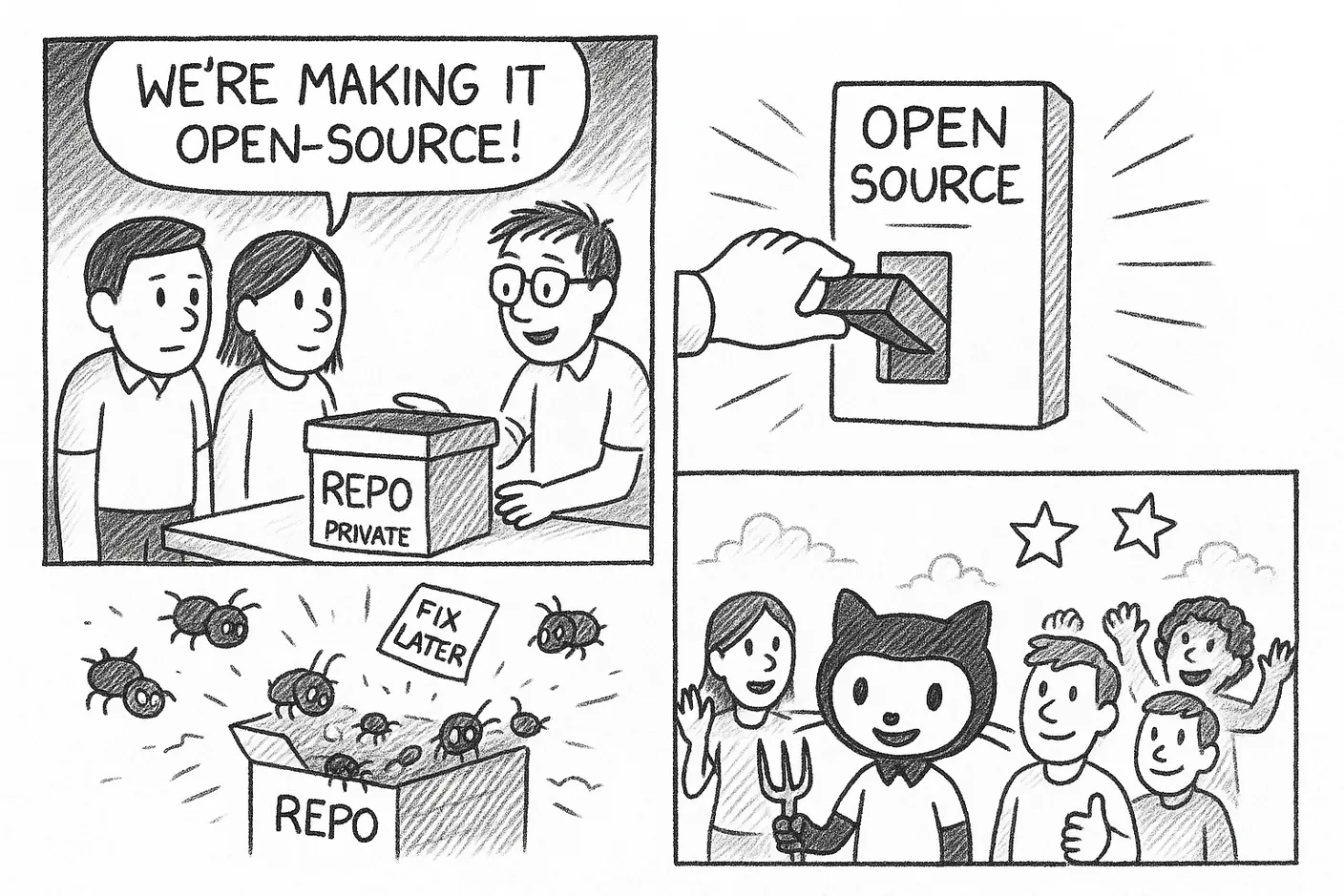

In this blog post we’ll take a look at how we open-sourced a part of FortID code. We’ll be focusing on the decisions that went into it, on both the business side as well as the technical one.

TL;DR The steps we took to go from “top secret” to “open-source” were:

- Rename

final_final_REALfinal.rsto something respectable. - Pretend it was always tidy.

- Beg for stars.

Joking aside, let’s start off with the motivation, why open-source at all?

Why Open-Source?

There are a couple of reasons for open-sourcing.

The first is making FortID more visible as well as credible on the market. We are a cybersecurity company first and foremost, so it is quite beneficial for everyone involved to allow easy access for people to poke holes in our system. We eagerly invite people to find and report issues with our code. This helps us build confident software while also building trust within the community.

The other, much stronger reason is that the EUDI Wallet technology is regulated by the REGULATION (EU) 2024/1183, and as such mandates some parts be open-source.

Let’s take a look at the current state of EUDI related open-source code.

Overview of EUDI Open-Source Projects

The main EUDI open-source project is the official EU Digital Identity Wallet repository. It is in active and rapid development, but nevertheless it is still not up to date with the latest versions of specifications. For example, at the time of writing, their EUDIW Issuer is undergoing a transition from OpenID4VCI draft 13 to 15.

Besides the official offering, there are many more projects in the works. Most of these are tracked through The OpenWallet Foundation which aims to facilitate global interoperability of verifiable credentials. At the time of writing, their list of projects shows that almost all of these are in the so called “Lab” stage, i.e. experimental or early stage.

We can conclude that the whole EUDI open-source ecosystem is in its early stages, so it is normal for things to be incomplete. This places us in a position to help advance the domain by providing our own solutions.

Furthermore, as we poke holes in other open-source projects by trying to interoperate with them, so can they poke holes in our own code. This is a net benefit for everyone involved, as we hope to get to a point where the EUDI framework is wholly implemented and tested. As of now, each project is in an incomplete state, so this leads to various interoperability issues. You can find out more about those issues on our blog.

Currently, we have open-sourced parts of our Rust code. We are one of the rare companies using Rust to develop EUDI components. The reason we are using Rust is a topic for another day, but safety and security is one of its integral strengths. Naturally, we hope to have our solutions be recognized as the most robust and secure.

Before we open-sourced our solutions and thus made them publicly known, we had to make some company wide decisions.

Business & Process Decisions

The first decision we had to make was choosing the license for the code we open-source. We knew we wanted to allow external contributions as well as allow people to modify the code and use it for their own specific use-cases. On the other hand, we wanted to set some restrictions. From the business perspective, it would be bad if someone were to just take our code and make a profit out of it without giving some credit to us. Furthermore, as we concluded in the previous section, we’d like to help advance the field. This leads us to want to restrict modifications such that they also need to be open-sourced. Thus, any new development built on top of our code will be visible to everyone in the EUDI domain. All of the above naturally leads us to the well-known GNU General Public License (GNU GPL) family of licenses. We opted for GNU Affero GPL (GNU AGPL) as it has a clause dealing with software running over a network, and we expect our software to be part of such services.

Another decision we had to make relates to our internal development process. We use Jira for tracking issues and features, but that is only accessible to employees. We would like to encourage external contributions to our open-source code, so any tickets pertaining that code should be publicly visible. GitHub has its own issue tracking system, so it makes sense we adopt that. The question was then should we duplicate the tickets in Jira with those on GitHub (and vice versa)? If we only track open-source code issues on GitHub and not in Jira, then we lose the unified view of things that are in progress as well as the workload of each developer. On the other hand, we simplify the process of creating and tracking issues by having a single source of truth — GitHub. We opted for exactly that, open-source code issues are only on GitHub. This makes it simpler for our developers while also enabling external contribution.

A not so obvious decision we had to make was how will our developers represent themselves on GitHub. Do they use real names? Should they have aliases? Or maybe they should use a single company account? The case for not using real names was that some developers would like to stay anonymous and preserve their privacy. On the other hand, not using real names may reduce the credibility of the open-source repository. After multiple internal discussions, we didn’t have a clear cut choice… So we decided to default to real names, but allow developers to have aliases if they so desire.

Now that we’ve settled on the business and process decisions, it’s time to take a look at the technical side of things.

Technical Decisions

In the company, we are using a mono repository for all of our code. The mono repo setup allows developers to easily view and make changes in multiple projects and/or modules. This is quite convenient when a developer wants to update multiple projects or modules that depend on each other. Naturally, the consequence of that is that multiple git commits in a sequence or even a single git commit may relate to multiple different modules. We generally avoid having a single git commit touch multiple modules. Nevertheless, this poses a question on how should we develop our open-source modules.

Do we continue the development in the mono repo and copy the relevant modules to the open-source repository from time to time? This would simplify the dependency management for us, and the development process would remain the same for most of the time. Couple of issues arise when copying things to open-source repo. If we simply copy the current state of the code and commit that, we lose the original log of commits. We could make a tool which would filter out commit messages in the mono repo which touched the open-source module and have them be part of the open-source repo commit. Still, we would lose the authorship information along with other potentially relevant history information. Overall, the open-source repository wouldn’t look as professional or trustworthy as we want it to.

The decision we then made was to forego our usual mono repo setup, and have the open-source modules be completely stand-alone in an open-source repository. The open-source repository we made is essentially a mono repo of its own for Rust code we open-source. Our internal mono repo doesn’t track/duplicate the open-source code, but instead relies on crates.io to fetch published versions of crates we open-sourced. Essentially, we’ve become the external users of our open-source crates as if we aren’t developing them. This does slow down our development process as we now have multiple repositories to manage as well as go through the official crates.io publishing process. On the other hand, we get clear benefits for the open-source community. Anyone can now contribute and see the complete development history of the open-source code.

With the repository setup decided on, let’s take a look at the code itself. As a company, we would like to represent ourselves the best way possible. That means that we would like to show this through our high quality work. Naturally, high quality work requires time and there are trade-offs to be made here. How fast do we produce things? What is the level of code quality we are comfortable showing? Internally, we already have some formal guidelines for writing Rust code. These are quite similar to Rust API Guidelines. We also have development guidelines which mandate code review, git commit message style, etc. Ideally, we would like to have all of these documents be public so that open-source contributors can be on the same page as us. Alas, at the time of writing, some documents are in the company’s private mono repository, while some are on Confluence.

Before open-sourcing our code, we took the existing guidelines we have and expanded them with some additional details. Those details mostly pertained the code documentation and packaging. For example, we settled on prefixing company Rust crates with bh as if making them a brand for easier recognition. We’ve also made hard requirements for having all of public API be documented. This is easy to enforce in Rust via #![deny(missing_docs)] directive. We hope to reach new users of the code, so it’s imperative things be documented. Another key thing for users is making the API easy to use, but hard to misuse. That’s a whole topic for another day. Besides the Rust code itself, we’ve also decided on how we structure README.md and CHANGELOG.md files.

In summary, we took our existing code quality bar and elevated it a bit, so as not to introduce too much additional overhead on our existing workflow.

Finally, we also wrote a CONTRIBUTING.md for our open-source repository. This document serves as an introduction for anyone outside of the company wishing to contribute. Essentially, the document is a mixture of our internal development guidelines discussed above, but boiled down to a simpler core set of guidelines for new developers.

Conclusion

With the open-source code in place, there are some long lasting consequences on software development in the company. Some of those are good, while some less so.

For starters, our development speed is slower when a component in our internal code requires an update in an open-sourced component. Previously we would just update both components and make one or two pull requests (PRs) on our private repository. Now the process includes more steps.

- Update the open-sourced component and make a PR in the public repository.

- Publish the code to crates.io.

- Make a PR in our private repository to use the newly published version.

- Update the internal component and make a PR in our private repository.

On the other hand, the fact the open-sourced components are publicly visible provides additional incentives for writing quality code. There’s much more emphasis on making the code easily (re)usable while keeping it hard to misuse. In our private repository we can easily change code and know exactly the users of our code. The same doesn’t hold for open-sourced code where we don’t know the users and we certainly don’t want to change things under their feet as often as we can with internal code.

Speaking of external users, we welcome you to take a look at our open-source repository. We encourage you to try using our code and please do not refrain from reporting issues, suggesting enhancements or hacking on the code itself!